|

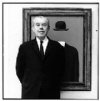

Artist > Rene Magritte (67 paintings.) |

Early life and career

Magritte was born in Lessines, in the province of Hainaut, in 1898, the eldest son of Léopold Magritte, who was a tailor and textile merchant,[1] and Régina (née Bertinchamps), a milliner until her marriage. Little is known about Magritte's early life. He began lessons in drawing in 1910. On 12 March 1912, his mother committed suicide by drowning herself in the River Sambre. This was not her first attempt; she had made many over a number of years, driving her husband Léopold to lock her into her bedroom. One day she escaped, and was missing for days. She was later discovered a mile or so down the river, dead. According to a legend, 13 year old Magritte was present when her body was retrieved from the water, but recent research has discredited this story, which may have originated with the family nurse.[2] Supposedly, when his mother was found her dress was covering her face, an image that has been suggested as the source of several paintings Magritte painted in 1927–1928 of people with cloth obscuring their faces, including Les Amants.[3]

Magritte's earliest paintings, which date from about 1915, were Impressionistic in style.[2] From 1916 to 1918 he studied at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, but found the instruction uninspiring. The paintings he produced during the years 1918–1924 were influenced by Futurism and by the offshoot of Cubism practiced by Metzinger.[2] Most of his works of this period are female nudes.

In 1922 Magritte married Georgette Berger, whom he had met as a child in 1913.[1] From December 1920 until September 1921, Magritte served in the Belgian infantry in the Flemish town of Beverlo near Leopoldsburg. He worked as a draughtsman in a wallpaper factory, and was a poster and advertisement designer until 1926, when a contract with Galerie la Centaure in Brussels made it possible for him to paint full-time. In 1926, Magritte produced his first surreal painting, The Lost Jockey (Le jockey perdu), and held his first exhibition in Brussels in 1927. Critics heaped abuse on the exhibition. Depressed by the failure, he moved to Paris where he became friends with André Breton, and became involved in the surrealist group.

Galerie la Centaure closed at the end of 1929, ending Magritte's contract income. Having made little impact in Paris, Magritte returned to Brussels in 1930 and resumed working in advertising.[4] He and his brother, Paul, formed an agency which earned him a living wage.

Surrealist patron Edward James allowed Magritte, in the early stages of his career, to stay rent free in his London home and paint. James is featured in two of Magritte's pieces, Le Principe du Plaisir (The Pleasure Principle) and La Reproduction Interdite, a painting also known as Not to be Reproduced. [5]

During the German occupation of Belgium in World War II he remained in Brussels, which led to a break with Breton. He briefly adopted a colorful, painterly style in 1943–44, an interlude known as his "Renoir Period", as a reaction to his feelings of alienation and abandonment that came with living in German occupied Belgium. In 1946, renouncing the violence and pessimism of his earlier work, he joined several other Belgian artists in signing the manifesto Surrealism in Full Sunlight.[6] During 1947–48—Magritte's "Vache Period"—he painted in a provocative and crude Fauve style. During this time, Magritte supported himself through the production of fake Picassos, Braques and Chiricos—a fraudulent repertoire he was later to expand into the printing of forged banknotes during the lean postwar period. This venture was undertaken alongside his brother Paul Magritte and fellow Surrealist and 'surrogate son' Marcel Marien, to whom had fallen the task of selling the forgeries.[7] At the end of 1948, he returned to the style and themes of his prewar surrealistic art.

His work was exhibited in the United States in New York in 1936 and again in that city in two retrospective exhibitions, one at the Museum of Modern Art in 1965, and the other at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1992.

Magritte died of pancreatic cancer on 15 August 1967 in his own bed, and was interred in Schaarbeek Cemetery, Brussels.

Popular interest in Magritte's work rose considerably in the 1960s, and his imagery has influenced pop, minimalist and conceptual art.[8] In 2005 he came 9th in the Walloon version of De Grootste Belg (The Greatest Belgian); in the Flemish version he was 18th.

Magritte's work frequently displays a juxtaposition of ordinary objects in an unusual context, giving new meanings to familiar things. The representational use of objects as other than what they seem is typified in his painting, The Treachery of Images (La trahison des images), which shows a pipe that looks as though it is a model for a tobacco store advertisement. Magritte painted below the pipe "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" ("This is not a pipe"), which seems a contradiction, but is actually true: the painting is not a pipe, it is an image of a pipe. It does not "satisfy emotionally"—when Magritte once was asked about this image, he replied that of course it was not a pipe, just try to fill it with tobacco.[9]

Magritte used the same approach in a painting of an apple: he painted the fruit realistically and then used an internal caption or framing device to deny that the item was an apple. In these "Ceci n'est pas" works, Magritte points out that no matter how closely, through realism-art, we come to depicting an item accurately, we never do catch the item itself.

Among Magritte's works are a number of surrealist versions of other famous paintings. Elsewhere, Magritte challenges the difficulty of artwork to convey meaning with a recurring motif of an easel, as in his The Human Condition series (1933, 1935) or The Promenades of Euclid (1955) (wherein the spires of a castle are "painted" upon the ordinary streets which the canvas overlooks). In a letter to André Breton, he wrote of The Human Condition that it was irrelevant if the scene behind the easel differed from what was depicted upon it, "but the main thing was to eliminate the difference between a view seen from outside and from inside a room."[10] The windows in some of these pictures are framed with heavy drapes, suggesting a theatrical motif.[11]

Magritte's style of surrealism is more representational than the "automatic" style of artists such as Joan Miró. Magritte's use of ordinary objects in unfamiliar spaces is joined to his desire to create poetic imagery. He described the act of painting as "the art of putting colors side by side in such a way that their real aspect is effaced, so that familiar objects—the sky, people, trees, mountains, furniture, the stars, solid structures, graffiti—become united in a single poetically disciplined image. The poetry of this image dispenses with any symbolic significance, old or new.”[12]

René Magritte described his paintings as "visible images which conceal nothing; they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question, 'What does that mean?'. It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing either, it is unknowable."[13]

Magritte's constant play with reality and illusion has been attributed to the early death of his mother. Psychoanalysts who have examined bereaved children have said that Magritte's back and forth play with reality and illusion reflects his "constant shifting back and forth from what he wishes—'mother is alive'—to what he knows—'mother is dead' "[14]

In popular culture

The 1960s brought a great increase in public awareness of Magritte's work.[8] Thanks to his "sound knowledge of how to present objects in a manner both suggestive and questioning," his works have been frequently adapted or plagiarized in advertisements, posters, book covers and the like.[18] Examples include album covers such as Beck-Ola by The Jeff Beck Group (reproducing Magritte's The Listening Room), Jackson Browne's 1974 album, Late for the Sky, with artwork inspired by Magritte's L'Empire des Lumières, and the Firesign Theatre's album Just Folks . . . A Firesign Chat based on The Mysteries of the Horizon.

Tom Stoppard has written a surrealist play called After Magritte.

Douglas Hofstadter's book Gödel, Escher, Bach uses Magritte works for many of its illustrations.

Paul Simon's song "Rene and Georgette Magritte with Their Dog after the War" appears on the 1983 album Hearts and Bones.

Magritte's imagery has inspired filmmakers ranging from the surrealist Marcel Mariën to mainstream directors such as Jean-Luc Godard, Bernardo Bertolucci, Nicholas Roeg, and Terry Gilliam.[19][20]

The painting "The Son of Man" is a prominent motif in the 1999 film about an art theft titled The Thomas Crown Affair and in the 2006 film Stranger Than Fiction.

According to Ellen Burstyn, in the 1998 documentary The Fear of God: 25 Years of "The Exorcist", the iconic poster shot for the film The Exorcist was inspired by Magritte's L'Empire des Lumières.